Or did he make it up? (Part – 2)

By : Niranjan Kambi, Department of Psychology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA

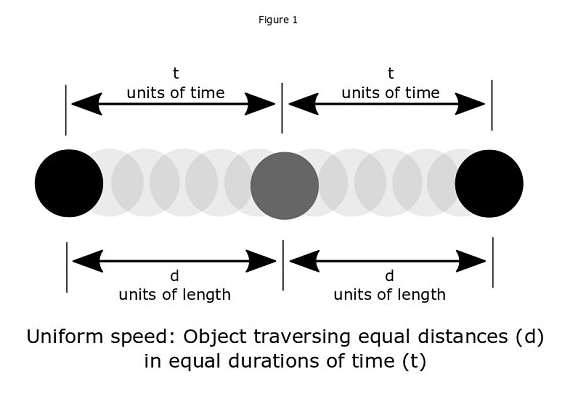

Newton, one of mankind’s greatest geniuses, expanded on Galileo’s insight and said the only way to break out of inertia is to apply force, that is, a push or pull to change the speed or the direction of motion of the object. He wondered if the motion of planets followed the same principle. Ancient thinkers, from Aristotle in the West to Brahmagupta in the East, had theorised that objects were attracted to the earth because it was in their nature to do so. Newton ignored this non-explanation, and applied the laws of motion to the motion of planets. So, what are the consequences of applying force to a moving object? If a push is applied in the direction of motion of the object, the object accelerates and vice versa. A sideward application of force changes the direction of motion.

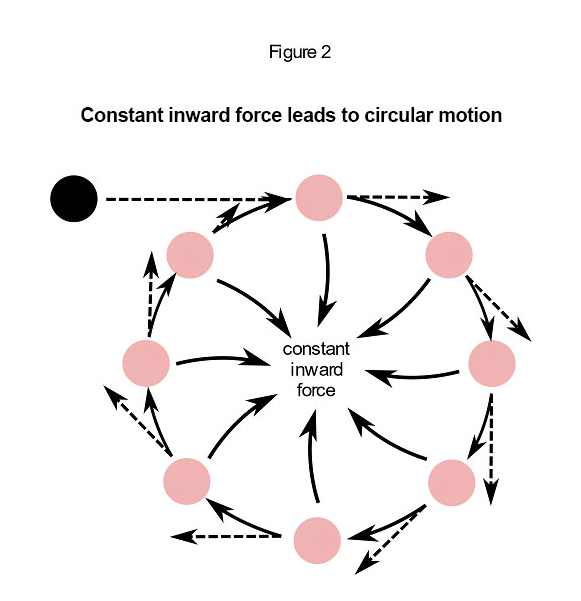

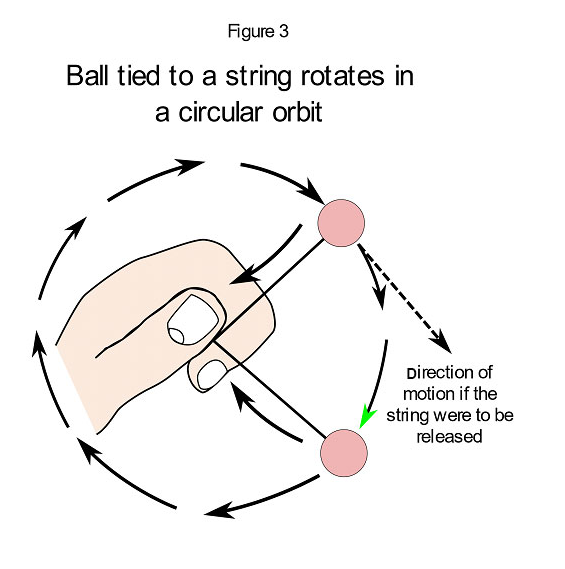

Let’s consider this application of force, as Newton did, in the case of circular motion. Visualise spinning a stone tied to a string. We must apply a constant force towards the centre to keep the stone spinning in a circle. Newton easily explained this by invoking his laws of motion. If left to itself, the stone would keep traveling in a straight line forever, assuming there was no friction or any other force acting on it. However, applying a constant inward or sideward force alters the straight path into a circular one. The natural direction of motion of the stone is apparent when the string is suddenly released. The stone escapes in a tangential direction indicating a constant force that was applied inwards along the radius while it was spinning in a circle.

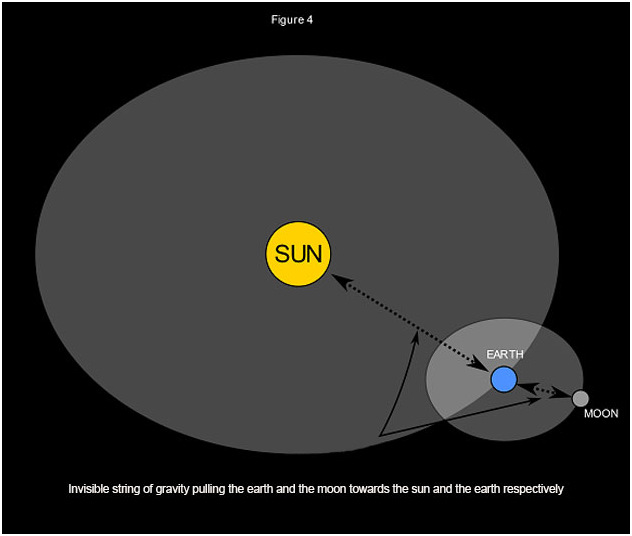

Coming back to planetary motion, Newton applied the same logic and concluded correctly that planets revolving in circular or elliptical orbits around the sun must always have some kind of force pulling them towards the center of the sun.

So, what’s the nature of this force and how is it transmitted between, say, the sun and a planet millions of miles away with nothing in between? In the case of the stone, it was the string that acted as the conduit for the force pulling it towards the centre.

This “spooky action at a distance” without anything connecting the two bodies was a far departure from the 17th century physical understanding based on mechanical philosophy as envisaged by the highly influential Descartes.

What’s mechanical philosophy? It’s the commonsensical view that an object cannot be displaced from its position without coming in direct contact with another moving body. Generalising this conclusion, every kind of change in our universe must have a mechanical or material cause. This system or philosophy, also called materialism, has been a dominant paradigm for scientific exploration of our universe, including understanding of the connection between the mind and the brain. However, this commonsensical worldview of materialism was dealt a body blow (pun intended) by Newton’s discovery that the sun and the planets attract each other without anything connecting them, a sort of “spooky action at a distance”, as the famous phrase attributed to Albert Einstein describes it.

To be continued… Next Week